About the Contributors

Maya Gjelhaug, Print Editor-in-Chief

My name is Maya, and I’m excited to be one of your print Editors-in-Chief this year. When I’m not editing articles, you can find me mountain biking and watching Band of Brothers with my dad.

Awards:

Best of SNO – Mounds View Theater casting sparks controversy

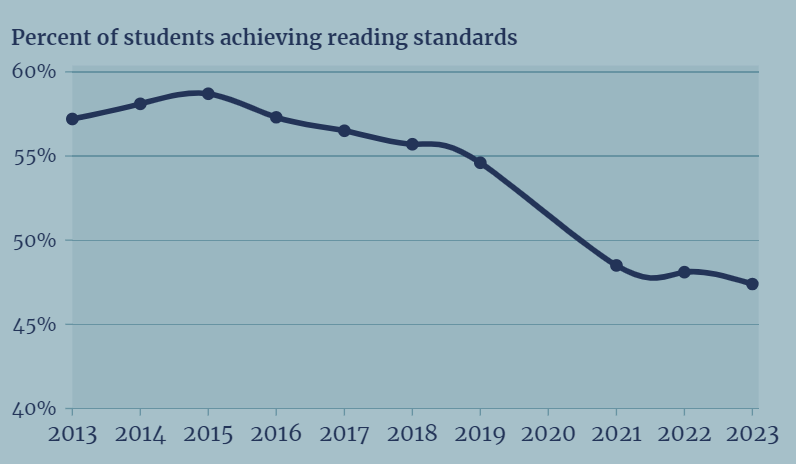

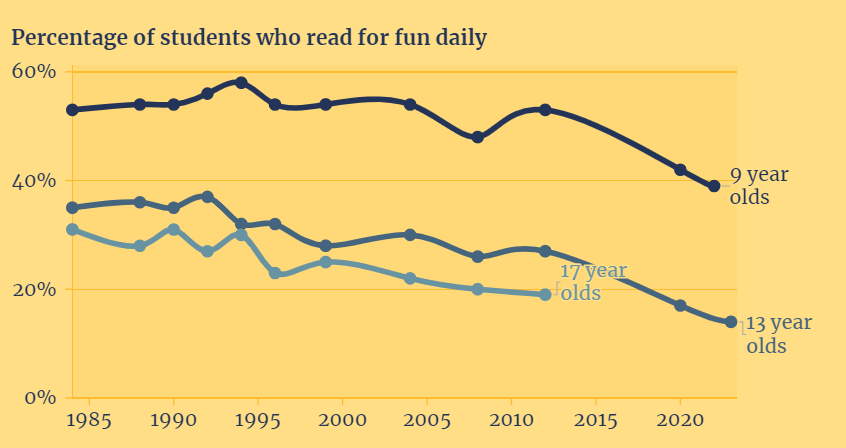

Best of SNO – The downfall of ELA education

Best of SNO – Pro-life activists rally against Minnesota abortion legislation

Best of SNO – Prince of Peace Church combats homelessness with tiny home settlement

Best of SNO – Should legacy admissions still exist?

2nd-Place Gold Medallion Spread – Youth sports culture

SNO Site Excellence Design Award

SNO Page Excellence Award

Isabel Li, Print Editor-in-Chief

Hi, my name is Isabel, and I am super excited to be editor-in-chief this year. Outside of the Viewer, I am a captain of the girls’ cross country team. I also enjoy playing violin and piano, listening to Noah Kahan, and taking photos. Don’t forget to pick up a copy of the Viewer, and stay tuned for some fire podcasts ;)

Vincent Meyer, Spread Editor and Online Managing Editor

Hi, I’m Vincent and I’m a senior! This is my second year on the Viewer and I work as the online managing copy editor and spread editor. In my free time, I enjoy spending time with friends and family as well as going outside. I became an editor because it’s a great way to write about real world events and play an active part in my community!

William Overbo, Staff Reporter

Will is a senior staff reporter, and this year is his first year on The Viewer.

Awards:

Best of SNO – The downfall of ELA education

Tyler Quattrin, Print Editor-in-Chief and Features Editor

Hello! I am thrilled to be a print Editor-in-Chief for my third year on The Viewer. Outside of The Viewer, I am a captain of the Mounds View Boys Swim and Dive team. Feel free to reach out to me directly at [email protected].

Awards:

Best of SNO – Mounds View Theater casting sparks controversy

Best of SNO – Pro-life activists rally against Minnesota abortion legislation

Best of SNO – From Mounds View to the MN Supreme Court: Chief Justice Hudson’s distinguished career

Journalism Day at The Guthrie runner up – ‘Dial M for Murder’ Revitalizes Hitchcock’s Classic at the Guthrie

Charlotte Krum, Good Questions Editor

Hi! My name is Charlotte, and I’m a senior. This is my second year with The Viewer. I’m very excited to be an illustrator and the Good Question Editor 2023-2034 school year! I enjoy playing tennis, figure skating, drawing and listening to music.