A deep dive into the new generation of conspiracy theories

In the depths of human curiosity — a superstitious realm where skepticism and fear can converge — conspiracy theories often form. A conspiracy theory is a belief or explanation that suggests a group of people, often secret but influential, orchestrate events behind the scenes for their benefit at the expense of the general public.

Conspiracy theories typically revolve around cherry-picking information to support the conspiracy’s narrative and disregarding evidence that undermines their ideals. They often feature vague or shifting explanations that adapt to new information. From the “moon landing hoax” to claims of a “stolen” election, these theories range from seemingly believable thoughts to straight-up absurd.

Human interest in conspiracy theories lies not only in the thoughts themselves but also in the psychological and societal factors that give rise to them. Tracing conspiratorial thinking through history, one can see that they often emerge when people want to maintain control or find answers during times of uncertainty, societal tension and political upheavals. From politics to teens to education, conspiracy theories infiltrate much of modern society.

Misinformation constantly circulates on the internet. For teenagers, discerning whether information is real or fake is becoming increasingly difficult.

According to Forbes, teens spend an average of almost five hours a day on social media, which creates more opportunities for them to be susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies.

One such example is Shane Dawson’s widely popular, teen-oriented YouTube videos that explore far-fetched theories, including iPhones secretly recording their owners, Chuck E. Cheese recycling pizza slices and claims that the deadly wildfires in California were due to a high-power, military-operated laser beam. Although he never explicitly agrees with any conspiracy theories, Dawson promotes this unverifiable information by leaning on the predominantly young fanbase that he built throughout a decade-long YouTube career focusing on content for kids and teens. By incorporating concepts familiar to young people, Dawson portrays conspiratorial thinking in a way that is palatable to teens.

Dawson is not the only one who spreads unverified information online. According to Statista, a survey on online misinformation conducted in December 2020 reports that 38.2% of people had inadvertently spread misinformation on social media. Senior Sean Carver primarily gets updated on current events through apps like TikTok and Instagram reels. “I spend at least two or three hours on TikTok, and that’s lowballing it admittedly,” he said. The content that is viewed on TikTok differs from user to user, and Carver offered further insight into some of TikTok’s content. “I actually see a ton of flat Earth stuff [on TikTok]. It’s really entertaining.”

While sometimes entertaining, the unverified information on social media can lead to far more serious consequences for teens. The Center for Countering Digital Hate found that 60% of 13 to 17-year-old Americans agreed with four or more harmful conspiracies — which included anti-vaccine statements, racist rhetoric and COVID-19 misinformation — in comparison to 49% of adults.

There is a reason why conspiracy theories are more popular with teens than adults: They provide explanations for confusing happenings in the world. Because teens often have less understanding of how the world works, they are more likely to believe the first thing they hear, even if it is false — a phenomenon known as anchor bias.

These findings explain why conspiratorial thinking was strong in the days of COVID-19 when fear swept the globe and lockdowns severed many teenagers’ social bonds. Teenagers leaned on far-fetched beliefs, such as the belief that 5G mobile phone networks caused COVID-19, to cope with the isolation of the pandemic. Many videos regarding this conspiracy theory spread on TikTok, with creators seeking to discredit people who presented evidence that contradicted their perspective on the matter.

The spread of these polarizing viewpoints further encourages conspiratorial thinking. With over 10 million videos relating to the “deep state” conspiracy on TikTok, the constant circulation of peoples’ testimonies fuels this conspiracy, which makes users more likely to be exposed to additional conspiracies. Such a phenomenon is an example of an echo chamber, an environment where users encounter beliefs that reinforce their already established thought processes and isolate them from outside perspectives.

Conspiracy theories gain traction on these apps as individuals cherry-pick information from their original source to reinforce assumptions they have already made. Senior Tswb Vang said, “I think conspiracy thinking is the opposite of critical thinking. Because a lot of it is just people impulsively taking in one thing they hear and creating a big thing about it. […] They just believe what they think is right.”

Teens start believing in conspiracy theories for a variety of psychological reasons, including the allure of exclusivity. “It’s so easy to just dive into these theories,” said junior Emily Ren. “You have this exclusivity. People who are joining these conspiracy groups feel like they know something that other people don’t, that they’re in on something, which adds to the entire glamor of it.”

The damage caused by the perpetuation of these unfounded beliefs has a significant impact on the way teens use the internet and search for clarity. There is some novelty in the more outrageous camps of conspiratorial thinking, but the distortion of realities can have a serious impact on the way teens perceive the world.

“Why am I the only person on this stage, at least, who can say that Jan. 6th now does look like it was an inside job, that the government lied to us for 20 years about Saudi Arabia’s involvement in 9/11, that the great replacement theory is not some grand right-wing conspiracy theory but a basic statement of the Democratic Party’s platform, that the 2020 election was in indeed stolen by big tech, that the 2016 election, the one in that Trump won for sure, was also one that was stolen from him by the national security establishment?” said GOP presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy in the fourth GOP presidential debate.

As shown in Ramaswamy’s claims, conspiracy theories are powerful weapons in the political terrain, leaving ingrained marks on the public and their decision-making. From casting doubt on the legitimacy of elections to attributing fatal events to unseen powers, these theories can be used in politics in many ways, including to gain media attention, undermine opponents and capitalize on mistrust to position themselves as outsiders challenging the system.

Politicians’ lack of transparency and clarity may lead to public belief in conspiracies. “When it comes to politics, if things don’t make sense on a surface level, then you kind of seek out [that] there has to be other reasons, some other nefarious reasons,” said Social Studies Teacher Justin Benolkin.

A primary example is the Watergate scandal. After the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, the Nixon administration’s initial denials and refusal to disclose key information led to widespread conspiracy theories, including a CIA prostitution ring and a deep state media plot to bring down Nixon. Later, investigations and release of information showed the depth of corruption within the administration, proving the conspiracies false.

Investigative reports reveal that those who dive into conspiracies often feel a profound sense of reassurance from knowing secret information. Theorists believe that with possession of this secret information, they can exert an impactful change and challenge established political narratives. Jitarth Jadeja, a former QAnon believer — a far-right conspiracy theory claiming that a cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles plotted against President Trump in the 2020 election — revealed that the members usually felt a sense of duty to reveal injustices and claims such as rigged voting systems and widespread election irregularities.

Political conspiracy theories can snowball into bigger issues over time. The mobbing of the capital on Jan. 6, 2021, serves as a primary example. Conspiracy theories of voter fraud — encouraged by former president Donald Trump and his allies — led to a violent and armed mob of Trump supporters storming the U.S. Capitol. As a result, multiple perpetrators and officers died or committed suicide after the event, including Officer Howard Charles Liebengood who died after three 24-hour shifts without sleep.

Another major consequence of political conspiracy theories is the rise of anti-Semitism. Many times throughout history, people have raised theories suggesting that Jewish individuals or entities wield disproportionate influence over global affairs, finances or governments. Examples include people accusing Jewish people of purposefully poisoning wells in 14th-century Europe from to causing the 9/11 terrorist attack.

The impacts of anti-Semitism can be seen in our own community as well. During the recent Roseville School Board election, one of the seven candidates, Vaughn Klingenberg, was an open anti-Semite and Holocaust-denier who had repeatedly harassed Jewish worshipers at local synagogues. He is also a proponent of sterilizing Jewish people and tattooing them with the Star of David, convinced that the Jewish community counters the “universalist humanitarian agenda.”

Although he was clearly the least popular candidate in the election, receiving 0.76% of all votes, and repeatedly criticized by Roseville’s superintendent, the 227 votes he did receive prove that anti-Semitism in the community extends beyond just Klingenberg.

For better or for worse, it is clear conspiracies have a way of mobilizing believers to participate in politics, often in ways that target specific groups or engage in destructive behavior. The upcoming 2024 presidential election, along with Trump’s return to the ballot, is sure to amplify conspiratorial thinking throughout the coming months.

A 2021 Stanford University study found that in a pool of 8,000 students ranging from elementary to college, over 80% of middle school students could not distinguish between an ad and a news story. This troubling statistic is only exacerbated by findings from the Adolescent Conspiracy Beliefs Questionnaire that belief in conspiracy theories starts to increase at age 14. Such findings illustrate the susceptibility of children to conspiratorial thinking.

Lack of education has been correlated with increased belief in conspiracy theories. Political scientists from the University of Miami found that around 42% of those in the study with only a high school diploma believe in conspiracy theories compared with 22% of those with a postgraduate degree. Poor analytical thinking skills can lead the less educated to believe content that provides easy answers and scapegoats specific groups. Education can combat this by helping children develop critical thinking skills and increasing their exposure to diverse viewpoints, which reduces the appeal of conspiracy theories.

Schools can work towards improving analytical skills by promoting media literacy instruction. According to a study conducted by Media Literacy Now in 2022, only 38% of respondents reported learning how to analyze media messaging in high school. “Requiring media literacy education in high schools at an advanced level is really important. Middle school media literacy didn’t teach you crap. […] Media literacy courses need to be nimble and able to adapt rapidly due to how fast the internet landscape changes,” said junior Quincy Shi. Although Minnesota does not currently require media literacy to be taught in schools, Senator Amy Klobuchar introduced a federal bill in 2022 — the Digital Citizenship and Media Literacy Act — which awards grants of up to $20 million to education agencies to advance and encourage media literacy for K-12 students.

However, education is not the only factor at play. “If you look at the studies, a lot of people who believe in conspiracies actually tend to be very educated people because they tend to already need to have some sort of knowledge,” said Social Studies Teacher Aaron Oseland. This can be seen, according to The Guardian, by how people with more education are more likely to rationalize their beliefs, as their previous knowledge can lead them to dismiss new information. On a psychological level, conspiracy theories also tap into the desire of people, no matter how educated, to be a part of a group or feel superior or unique in their beliefs.

Misrepresentation from news outlets also factors into the appeal of conspiracy theories. “I think one of the biggest things that news sources do — which isn’t new — is a fallacy to think that we have to give equal weight to equal ideas. […] And I think that leads to people having a false idea that more people disagree with an idea than don’t. So for instance, […] nine tenths of all experts in the field of voter security would say [the election stealing of Donald Trump] is absurd, but on news programs, you don’t see every nine people interviewed say it’s absurd versus the one person who says it’s not,” said Benolkin. News organizations could consider this to prevent inflating unpopular and unsupported beliefs.

Another way to counter the spread of conspiracies is by advocating for fair and factual media. During the Jan. 6 insurrection, Facebook was arguably complicit by providing a platform to election-denying organizations as well as rampant misinformation. Social media platforms could work to counter misinformation and hate speech by using automated and human-driven editorial processes to detect false and harmful content.

In addition, social media platforms can fight misinformation with information. Instagram recently began including a description on posts flagged as misinformation which informs users about the current facts surrounding controversial events. This approach avoids censorship while encouraging users to willingly abandon conspiratorial beliefs.

Conspiracy theories persist in society, often due to a lack of education and their prevalence in the media. With the dangerous impacts of events fueled by conspiracy theories, increased education and regulation may be a key component to prevent them from happening.

-

SpreadWhat happens when religion meets education?

SpreadWhat happens when religion meets education? -

SpreadClimate change: the clock is ticking...

SpreadClimate change: the clock is ticking... -

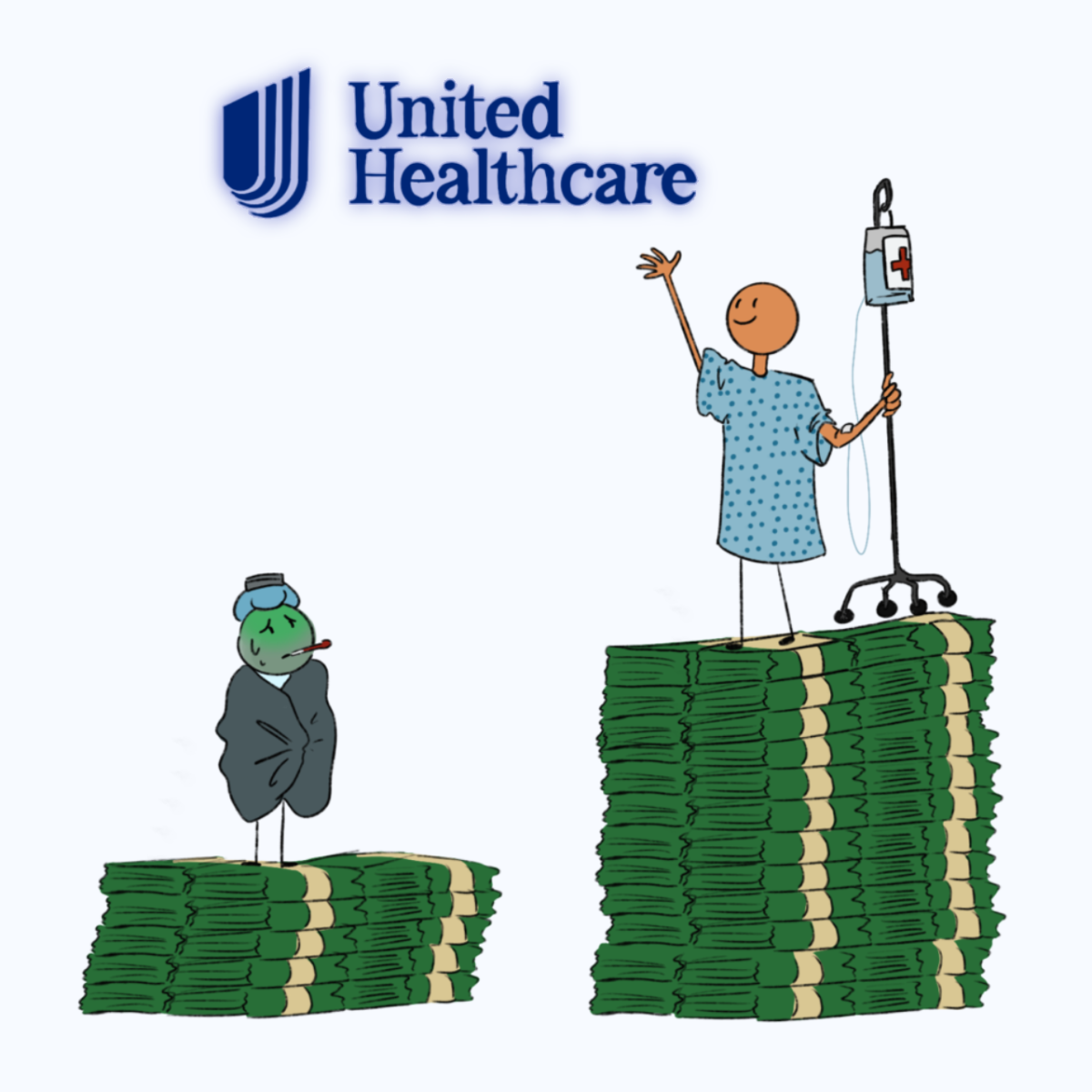

SpreadThe Healthcare Crisis: sky high prices

SpreadThe Healthcare Crisis: sky high prices -

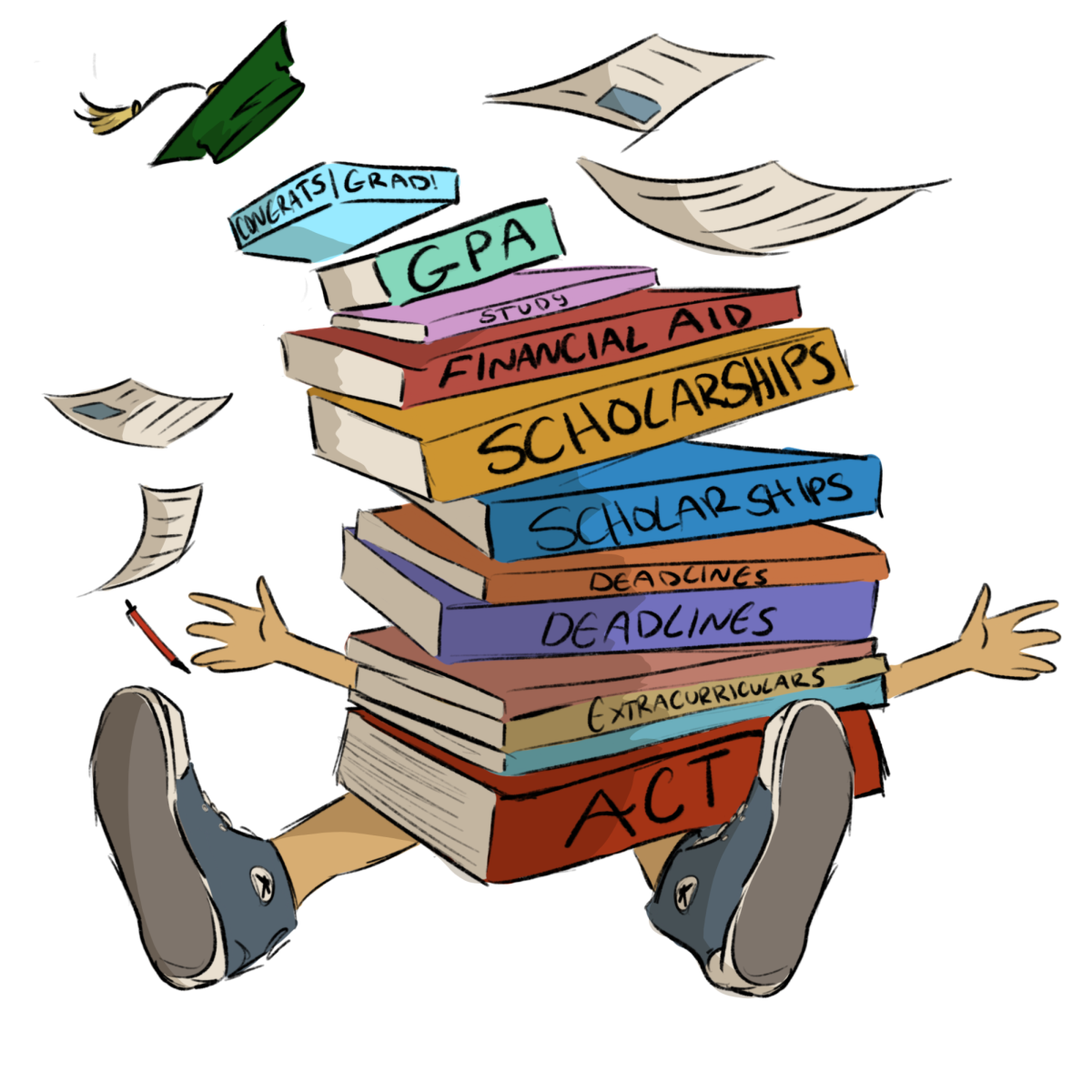

SpreadThe overwhelming culture of college applications

SpreadThe overwhelming culture of college applications -

SpreadSchool security

-

Spread2024 Presidential Election

Spread2024 Presidential Election -

SpreadMounds View celebrates 70 years

SpreadMounds View celebrates 70 years -

SpreadThe rising trend of overconsumption

SpreadThe rising trend of overconsumption -

Spread[COLLECTION] The rise of sports betting

Spread[COLLECTION] The rise of sports betting -

SpreadThe downfall of ELA education

SpreadThe downfall of ELA education