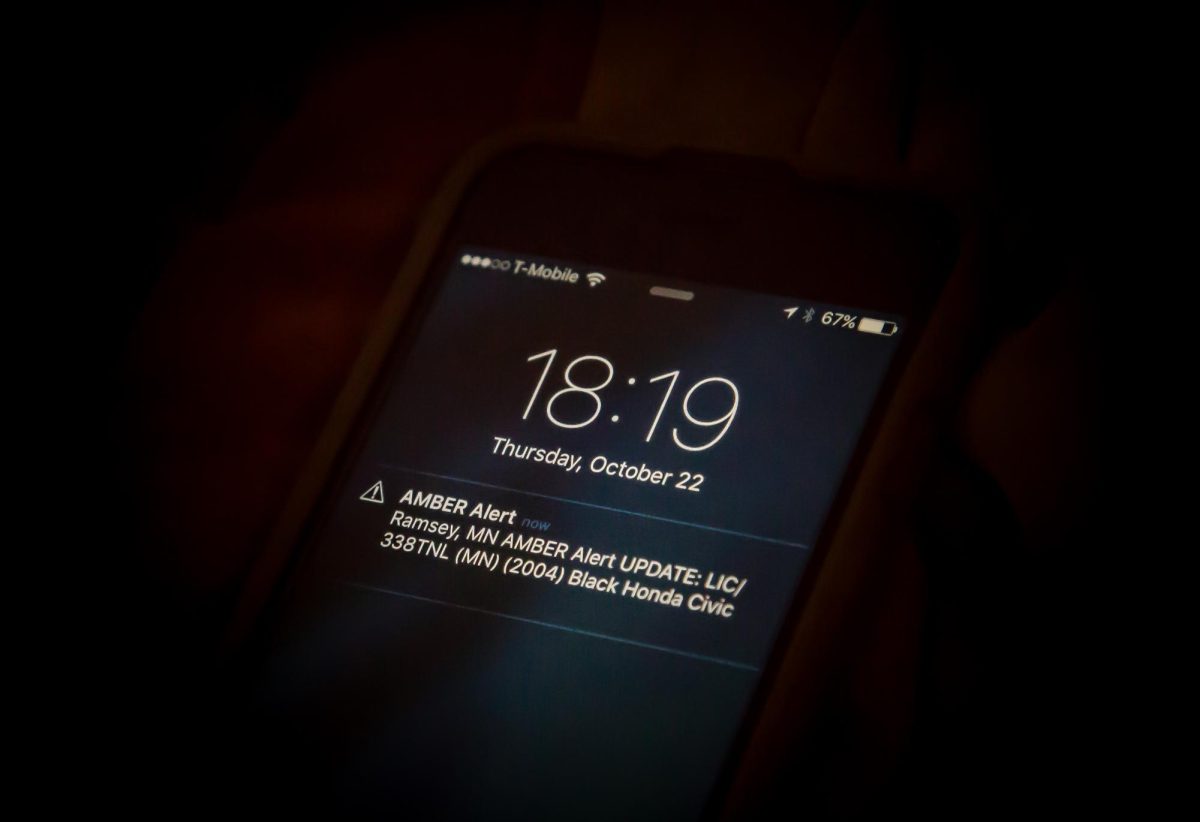

We receive a variety of alerts through our devices, one being the “America’s Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response” Alert, commonly known as the Amber Alert. It is a notification system warning us of child abductions, which, by most of us, is remembered as a blaring alert with a short description of the victim. It causes immediate anxiety, but it is also forgotten shortly after, as we usually assume the best-case scenario. However, the system is not that helpful.

The system was first established in 1996 in honor of Amber Hagerman, a nine-year-old from Arlington, Texas who was abducted and murdered. In hopes of saving future victims, the Dallas-Fort Worth broadcasters and the police developed the Amber Alert system, and it has now evolved into what we know today. However, the system’s effectiveness is unclear.

According to Pacific Standard magazine, the Department of Justice claims to have helped countless children with the use of the alert. More recently, 500 saved child abductions have been credited to the system. However, according to a report from Sage Journals and other critics, the notification system isn’t as reliable as these claims make it out to be.

Suppose we have a situation where the abductor has no intention to harm the child. For example, often, parents kidnap their children to protect them or to hurt the other guardian. In such a case, the alarm is more effective as there is an absence of risk, and so, search parties can focus their energy on finding the abductee. However, Amber Alerts have not saved many victims in cases where the child is kidnapped for the purpose of being harmed. According to Jack Levin, even when the child is rescued successfully when the Amber Alert is used, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the alert itself is what saves the child.

In addition to reliability, there is the question of when the alert can be requested. The requirements are: Law enforcement must confirm that a child has been abducted and that the child is at risk of serious injury or death, there must be sufficient and descriptive information about the child, abductor and the vehicle, and if the abductee is of 17 years or younger. When toddler King Walker went missing in Gary Indiana, his family expected an immediate Amber Alert to be issued. Unfortunately, the request was denied as the case did not meet set requirements. It’s ridiculous that children who have no control over abductions are checked against these requirements for the alert to be issued.

Some people, such as David Thelen, CEO of the advocacy group Committee of Missing Children, argue that using the system continuously can create “Amber Fatigue” and desensitize the mass population to urgent alerts, which encourages criteria for Amber Alerts. However, another perspective is that people should not filter Amber Alert requests. It is wrong for any of us to deny a plea for help because of the situation of the victim.

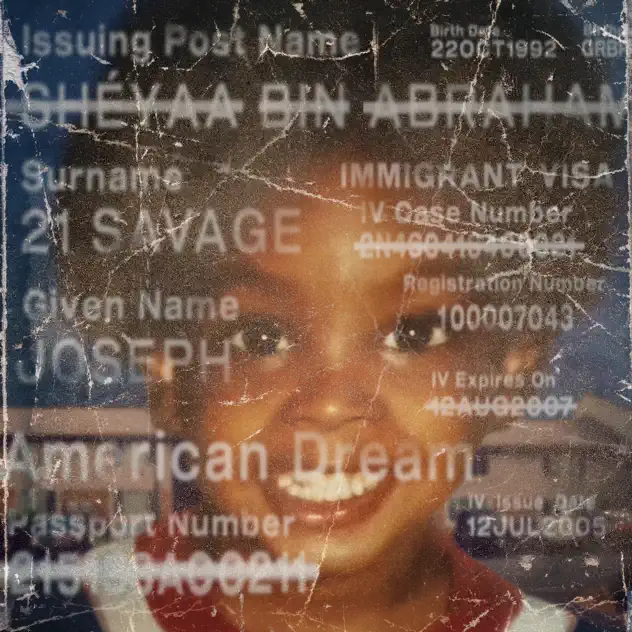

The race of the child is another factor to consider. According to USA Today, from 2017 to 2021, 41.5 percent of the alerts were for white children, 36.5 percent were for black children, 14.4 percent for Hispanic children, and less than 5 percent for other races. In addition to the disproportionate number of alerts issued by race, the Black & Missing Foundation claims that Amber alerts issued for black children may be delayed because police didn’t take it seriously or because of black families’ distrust in the police. Having such high levels of distrust in the police that families hesitate to ask for help defeats the whole purpose of the alert system.

Unfortunately, in addition to the police force, the media and receivers of the alerts are also more likely to view white children, especially girls, as more important victims, which in turn lowers the chances of black children being found.

Although Amber alerts aren’t as effective in finding abducted children as claimed, the intentions behind the system mean well. So it is important not to overlook the system’s issues and work towards improving the notification system. This way, we won’t have misplaced hope in a method that doesn’t aid others.

![[DEBATES] Prestigious colleges: value or hype?](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/buildings-1200x654.png)

![[OPINION] The dark origins of TikTok's looksmaxxing trend](https://www.mvviewer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Copy-of-Copy-of-Untitled-Design-1200x675.png)